Creative Loafing (a publication with a great name in Atlanta): For all the nattering gas-industry lobbyists and radio talk-show "skeptics," the scientists who actually study global warming overwhelmingly come to the same conclusion: The air is getting warmer, the seas are rising and the costs of climate change are likely to far outweigh the benefits. Ask experts how they envision a Georgia as the climate changes, and they paint a portrait of a state unlike the one we know today. "If we don't do anything at all [in regards to global warming], Georgia's going to be a much different place," says Ron Carroll, director of science at the University of Georgia's River Basin Center.

Creative Loafing (a publication with a great name in Atlanta): For all the nattering gas-industry lobbyists and radio talk-show "skeptics," the scientists who actually study global warming overwhelmingly come to the same conclusion: The air is getting warmer, the seas are rising and the costs of climate change are likely to far outweigh the benefits. Ask experts how they envision a Georgia as the climate changes, and they paint a portrait of a state unlike the one we know today. "If we don't do anything at all [in regards to global warming], Georgia's going to be a much different place," says Ron Carroll, director of science at the University of Georgia's River Basin Center. The changes are easiest to guess along the coast. According to a recent report from an international consortium of scientists, sea levels – the detail most often discussed when scientists describe the catastrophic changes of global warming – could rise at least three feet sometime between the middle and the end of the century. Georgia has a relatively shallow shore, which means rising water would spread farther inland than along steeper shorelines. Carroll foresees the shoreline shifting more than a mile. Once-prime real estate could become waterlogged and worthless. The barrier islands, already endangered because of development, may dwindle or become partially submerged by the rising ocean.

Nobody truly knows how much sea levels might rise. That partly depends on how quickly glaciers melt as far away as Greenland and Antarctica. But the local climate and ecological changes are even more difficult to predict. Georgia Tech atmospheric scientist Judith Curry and her colleagues got national attention shortly after Hurricane Katrina because they happened to publish a study around the same time that found more strong hurricanes have accompanied the global warming that already has taken place. Curry says continued warming may increase the likelihood that a violent storm could strike Georgia's coast, which has been spared a major hurricane since 1890. "With all the development along the shore, [a hurricane] would be a major wipeout," Curry says.

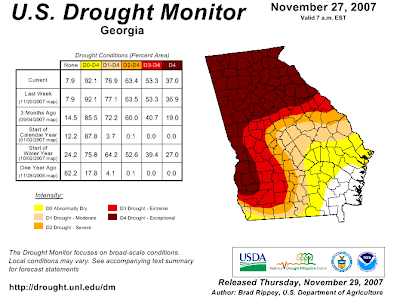

Inland weather is likely to become more extreme as well. "We'll have hotter, much more muggy summers," says Carroll, who's been studying climate change since 1999. Some computer models say the hottest days will be arid, making the state more at risk for forest fires. The long-term stress from prolonged droughts could result in Georgia's forests giving way to grasslands. But because heat agitates the cycle of evaporation and rainfall, storms are likely to come in violent bursts. It's difficult to say how such weather might affect wildlife, plants and even diseases. Warmer surface temperatures could make stagnant pools of water in dried-out rivers ideal breeding grounds for a variety of mosquitoes, each "competent vectors," as Carroll calls them, of a smorgasbord of diseases more commonly associated with tropical climates. He worries most about West Nile virus, encephalitis and Dengue fever, a mosquito-borne illness characterized by high fevers, body pains and rash. Its host, the Aedes aegypti fly, would find hotter environs more hospitable.

Not all the likely outcomes are quite so bleak. Slightly higher temperatures, longer growing periods and increased CO2 levels may mean greater yields for crops such as peanuts, soybeans and cotton – although such benefits would subside as temperatures continued to rise. The loblolly pine, Georgia's arboreal cash crop, could grow larger and stronger. According to one U.N. study, even roads may benefit – they may require less maintenance during the warmer winter.

Dr. Rhett Jackson, a hydrology professor at the University of Georgia, says that for all the talk of sea-level rise, the coast's productive estuaries are one example of an amazingly resilient ecosystem. Shrimp, blue crabs, oysters and other commercially valuable species that use the estuaries as nurseries may acclimate if sea levels rise. It's a different animal Jackson's worried about. "I think the species that'll have the hardest time adapting is us," he says. "We've built a civilization that is reliant on static conditions."

No comments:

Post a Comment